CW: unreality, paranoia, schizophrenia, psychosis, suicide, graphic depictions of violence, mind control, delusions, gaslighting, experimentation, child abuse, medication

“Bandersnatch” is perhaps the single most triggering episode for me in the entire collection of shows I’m watching for this project. Its themes are painfully resonant considering I too have been isolated plugging away at this fucking never-ending dissertation that everyone keeps telling me to simplify but I don’t know how to simplify because it’s all important—right, sorry, anyway the other reason it’s hard to watch is that it directly implicates the audience in ethical decisions in relation to the characters. As an interactive choose-your-own-adventure, you are prompted throughout to choose between two options, decisions Stefan perceives as being made for him and tries to resist with varying degrees of success. However, the central theme of the episode is the illusion of free will and how the narrative is structured in such a way to make all the decisions for you—as most stories are, although few let you pretend you’re in control. In fact, “Bandersnatch” was one of the main impetuses for looking at the triangular relationship between creators, characters, and audiences: the creators make decisions that affect the audience who make decisions that affect the characters who in turn make decisions that affect their own audiences as creators. Ultimately, all stories are crafted through the mutual collaboration (however contentious) between these positionalities, but different stories are characterized by different degrees of nominal and actual control among the parties. In “Bandersnatch”, the perception of choice masks the ways that creators haven’t actually given up control of the narrative, and that Stefan and the audience are doomed to make the same constrained mistakes.

“Bandersnatch” is one of the few episodes for which we have a definitive date, 9th July 1984, and is the only one set in the past instead of the near future (spoilers for "San Junipero"). Therefore, it’s the only one where despite appearances events are fixed—this is not a preventable future but a story that has already happened (several times as the iterations pile up). No matter what decisions you make, and allowing for slight changes in details, there is no ending where Stefan is both successful and sane. You could theoretically stop playing/watching after the first iteration where (if you start by agreeing to join Tuckersoft in-house) Bandersnatch is panned for feeling “designed-by-committee”, which is perhaps the most compassionate ending. (Also, just as a reminder, because “Bandersnatch” has so many pathways and combinations, I’m literally referring to a different version of the story than you might have experienced, and my analysis hinges on the way I personally played the game. This post may say more about me than it does about “Bandersnatch”.) But the point of the story, Stefan’s raison d’être, is the descent into madness: “I should try again. I’m trying again.” This moment, set in December when the game has released, is actually quite strange because it is the first to loop back to July 9th—what does Stefan mean by ‘trying again’? What if anything does he do in 1985? Or does he know he’s shifting to a different reality already? The cinematic cut deftly sidesteps this question because from a Doylist perspective we know why he’s trying again and what that means for us, but the splicing indicates the moment the story goes off the rails, where time is out of joint.

What’s purposefully frustrating about “Bandersnatch” is that there are no healthy options, and every time Stefan tries to do the healthy thing or his support system encourages him to do so, the options available to the audience do not allow for this. Several characters express concern when he decides to write the game on his own from his own room, knowing this will cause him to become isolated and obsessive. Colin is more on board with this the second time around (if you accept first)—“When it’s a concept piece, a bit of madness is what you need, and that works best when it’s one mind”—and the other characters let him go through with it, but as he deteriorates they get more adamant about trying to intervene. For example, when he yells at his dad, he tells Stefan, “I think the healthiest thing to do is to talk about any concerns you may have instead of bottling them up inside.” His dad insists he see his therapist, Dr. Haynes, and she encourages him to talk through his delusions and about his mother, the anniversary of whose death is approaching. She ups the dosage on his meds, but when he goes to take them, the audience is prompted to choose for him and is only given the options “Flush Them” or “Throw Them Away”. Even if you refuse to choose, the game chooses for you and defaults to the first option. The only way for Stefan to receive a happy, healthy ending is to leave the game incomplete on both levels. Like WarGames before it, “The only winning move is not to play.”

In the ending where he has completed the game after chopping up his dad’s body, Stefan concludes he was “trying to give the player too much choice,” and that letting the player think they were choosing was far simpler. This is also the entire point of the episode itself: despite being an interactive choose-your-own-adventure, your free will to substantially change the outcome is effectively an illusion granted by the creator. You are given at most two options, and if you refuse to choose, it will choose one for you. At some points, mostly in Stefan’s past, you are only given one option that is presented as a choice but is mostly presented as a courtesy. This implicates the audience in the decision even if they have no tangible effect on the outcome. Many of the decisions are inconsequential or trivial, such as what cereal to eat or what music to listen to. At other times, you are presented with identical options: “Tell Him More” or “Try to Explain”; “Throw Tea over Computer” or “Destroy Computer”; “Yeah” or “Fuck Yeah”. When you reach a dead end, it will prompt you to choose a new point of departure, and only sometimes will you be given the option to Exit to Credits. And even when you are given a meaningful choice, other characters will negate that choice, such as when Colin drugs you, or pressure you to choose a different option, such as when Dr. Haynes says: “Think again. You really might learn something new. So I’ll ask again: would you like to talk about what happened with your mother?” Or most blatantly, if you choose to accept Thakur’s offer Colin says “sorry mate wrong path”.

This deterministic framework spreads like a contagion from Davies to Stefan to Pearl to the viewer, and the more they/we get locked in a false dichotomy of two choices, as literalized by the symbol (which for convenience I will type as { given the similar shape and purpose), the more hopeless things seem. Perhaps this is why the first time we see it in the episode (it previously appeared in "White Bear"), it is graffitied on a billboard with the phrase “no future”, a phrase that has an added valence for queer theorists as the title of a book about queer refusals/impossibilities of futurity (Edelman). As we talked about, there is literally no future here, but that in turn suggests an indifference to the immutable past: “We’re on one path. Right now, me and you. And how one path ends is immaterial. It’s how our decisions along that path affect the whole that matters.” As Judith, narrator of a documentary on Davies, notes, “If you follow that line of thinking to its logical conclusion, then you’re absolved from any guilt from your actions. But they’re not even your actions. It’s out of your control; your fate has been dictated, it's out of your hands. So why not commit murder?”

This implicates the audience by shifting some of the moral responsibility for these choices onto the ones doing the controlling, though they are still clear that Stefan must be held accountable for his actions. The fact he wasn’t in full control of his faculties will affect his sentence (it’s why we have the insanity plea), but it can’t erase the material fact of having killed his father. Nevertheless, Stefan demands accountability from us as well, if only in the sense of acknowledging the existence of a relationship. At first, he is simply surprised at his actions, such as when you refuse Thakur’s offer: he says no with a smile then starts, having clearly intended to say yes. He begins to resist instructions such as biting his thumb, and eventually he demands a response from the audience in the form of the computer terminal. Whether you present yourself as a viewer from the future, a representative of PACS, or simply { , you and Stefan become permanently entangled, and he knows that you’re partially to blame for how fucked up his life is (see Barad). For me personally, that responsibility weighs on me—I apologize to the characters and every time I play I try to make what I think are the most ethical choices, not necessarily the best story choices. But again, the audience is also being controlled by the terms of the story world: the options presented to us have no real consequence because the story is already told. “So why not commit murder?” In this sense, there is a level of responsibility on the part of the creator, the audience, and the character for the mutual construction of the situation. In this type of story, the creator has the most power to shape the world, the audience limited power, and Stefan vanishingly little power. Because observation traps characters into the story, as long as we keep watching/playing, they are beholden to whatever the story does to them, and they can either resist or accept. In the end, Stefan stops resisting, though he does complain (rightly so):

Stefan: “What do I do?”

You: “Bury Body”

Stefan: “Okay”

Stefan: “What do I do?”

You: “Chop Up Body”

Stefan: “Oh god, really?”

And again, the show is quite clear about trying to get the audience to ask the same questions: you are being given the illusion of choice regarding Stefan. Will you accept the terms of the reality presented to you, or will you resist them (refusing to watch, watching incorrectly, choosing more ethical-seeming pathways, skipping steps, trolling, etc.)? Deny Pax or Worship Pax?

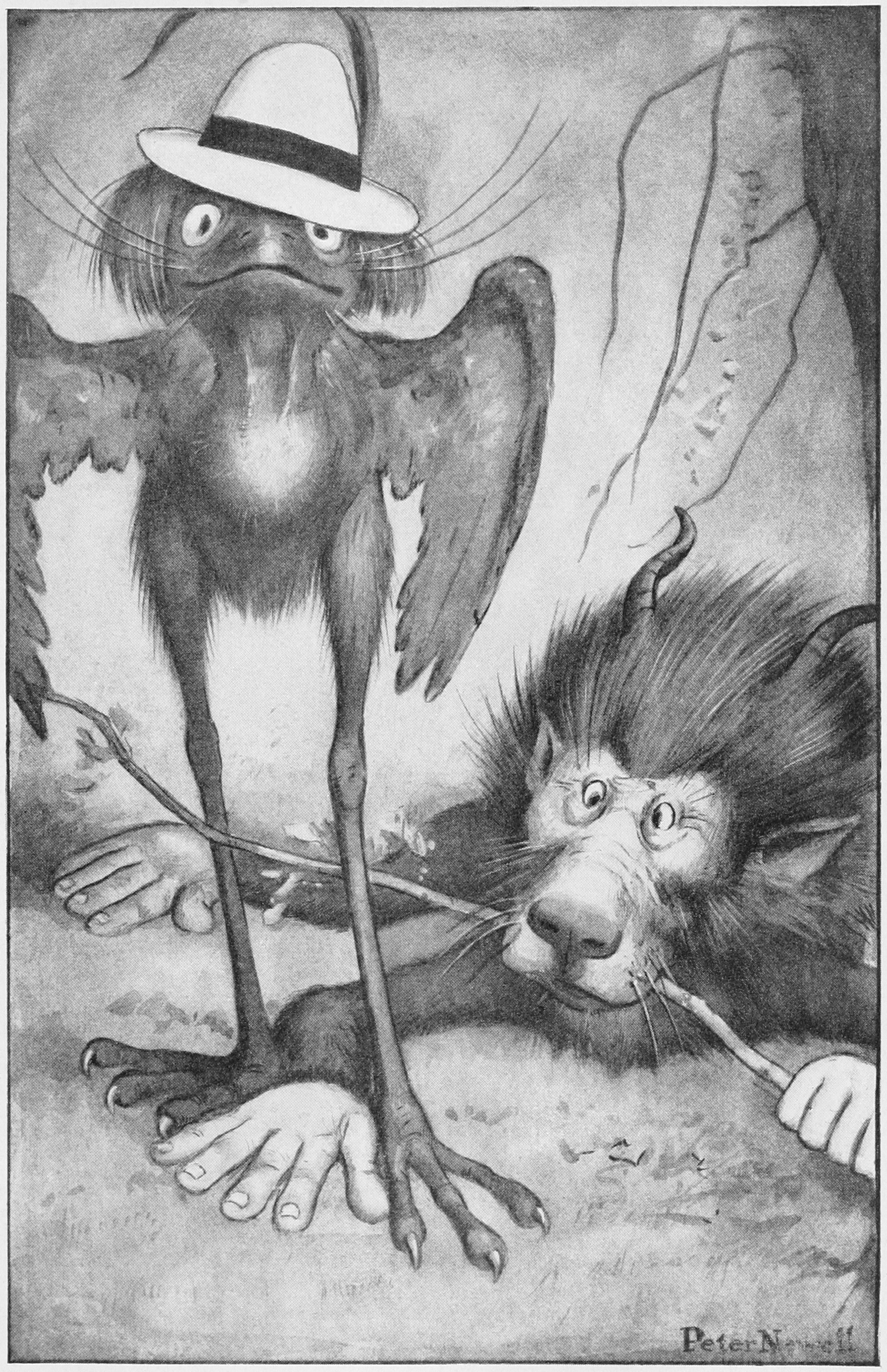

By the rules of “Bandersnatch”, ultimately the player is an agent of (or is) the demon Pax in relation to the characters (eventually in the scene where you talk to Stefan, you are able to present yourself as PACS). Pax is the antagonist in the book and game as well, and so in each iteration of the story Pax is hiding behind the corners of the labyrinth of choices. Pax is also the titular Bandersnatch; throughout the episode, there are references to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. Young Stefan is constantly searching for the white Rabbit stuffed animal his dad confiscated (Stefan is also queercoded at points such as when his dad says dolls are for sissies), and when he finally finds/catches the rabbit, he dies with his mom: “You put [rabbit] back where he belongs”. (Personally my theory is that Stefan was supposed to die in the train crash and the reason shit goes south in all these pathways is that Pax/PACS spared him—he is the “Thief of Destiny” after all.) Colin tells us that “mirrors let you move through time”, which is how Stefan returns to his mom. And of course, there’s the titular Bandersnatch, a creature first mentioned in the poem “Jabberwocky”: “beware the Jubjub bird and shun the frumious Bandersnatch” (Carroll 149). Carroll explains ‘frumious’ to mean both furious and fuming, and the Bandersnatch is described elsewhere as being fast with snapping jaws. The design of Pax seems to be based on some of the illustrations done for early editions of the book (see Peter Newell illustration below). He best resembles a lion, and lion imagery is present throughout. There is a drawing of Pax on the drugs Colin gives Stefan, and while he’s coding we often see the sprite of Pax on the screen. He holds up his model for Pax while the documentary plays and tells him he has no control.

The lion imagery is also heavily associated with Thakur. He asks Satpal for a Lion Bar, and in every timeline he chooses Worship Pax for you: by continuing to play, you can no longer Deny Pax. Thakur (pronounced Tucker) is the founder of Tuckersoft, which is basically the evil future tech corporation throughout Black Mirror. This aligns Pax with Tuckersoft, and Thakur’s offer to work there becomes a Deal with the Devil. The only way for Davies and Stefan to complete their versions of Bandersnatch was to offer a sacrifice to Pax: Davies’s wife and Stefan’s dad respectively. Pax also becomes a pun on PACS: Program and Control Study, the government program that has been studying/manipulating Stefan his whole life through his ‘dad’ (its crest is also a lion). The government is the corporation is the devil. Colin argues that PACMan stands for Program and Control Man, and Pacman’s navigation of the maze is how Colin describes their fate to Stefan. By continuing to play, we are Program and Control, we are Pax.

All this said, to assume that the exact same ethical frameworks obtain for interactions with people on the same plane as us (‘real’ people) and for people on other planes transmersed with ours (characters and higher powers) is itself an anthropomorphizing project (Publius). Materially, at least in our plane, characters and higher powers are definitionally not human—they are characters and/or higher powers: ceci n’est pas une pipe (Effe x). Ample research on violence in video games, among other topics, shows that there is no 1:1 correlation between in-universe violence and extradiegetic violence; conversely, there are also documented tangible cumulative effects of harmful media, such as stereotypes and propaganda. But while both arguments are important, they both sidestep the question of what precisely we owe to the characters themselves and vice versa. Is it always immoral to write tragedy? Is it always moral to give the character a happy ending? Must we always assume characters to be incapable of consent given possible power imbalances, and consent to what exactly? Is it ethical to insert yourself into the narrative through metalepsis (Effe xii)? And most importantly, why do we even tell this story in the first place (or as we say in dramaturgy, “why this play now?”), and why is it important that these things happen to these characters?

“How many times have you watched Pacman die? Doesn’t bother him, he just tries again.” Does it bother him? If so, what then? If not, what then? {

Works Cited

Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke UP, 2006.

Carroll, Lewis. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass. 1865/1871. Wordsworth Editions, 1993.

Edelman, Lee. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Duke UP, 2004.

Effe, Alexandra. J.M. Coetzee and the Ethics of Narrative Transgression: A Reconsideration of Metalepsis. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Publius, Xavia. “We Other Fairies.” Intonations vol. 1, no. 1, 2021, pp. 61-82.